By Corrine Folsom-O’Keefe (Audubon Alliance) and Amanda Pachomski (Audubon New York)

(Note: Scroll to the bottom of the page to view images)

In Connecticut, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) began monitoring Piping Plovers in 1986 when the species first received protection under the Endangered Species Act. The Connecticut Department of Energy & Environmental Protection (CT DEEP) Wildlife Division added their expertise with the passing of the Connecticut Endangered Species Act in 1989. The Audubon Alliance for Coastal Waterbirds joined the USFWS and the Wildlife Division in 2012. With the help of an amazing group of volunteers, these organizations have been stewarding Piping Plovers and other beach-nesting birds along the Connecticut shoreline for nearly 30 years. Working together, staff, field technicians, and volunteers exclose nests, protecting them from predators; put up string fencing to reduce disturbance in nesting areas; and engage beachgoers and municipalities by providing information about beach-nesting species, the threats they face, and how to help. Through these efforts, the number of pairs of Piping Plover nesting in the state has slowly increased.

Protecting Piping Plover on their nesting grounds is very important to species recovery, but we also need to think about the species and the habitat it uses during migration and over the winter. Historically, little has been known about the locations used by Piping Plover in winter. The 2006 discovery of 400 Piping Plovers in the Bahamas by the National Audubon Society and the Bahamas National Trust triggered a closer look at the nation’s 700 islands and roughly 2,000 cays. During the 2011 census, researchers found over 1,000 Piping Plovers—perhaps 20 percent of the entire Atlantic Coast population—concentrated in one small cluster of Bahamian islands—Andros Island, the Joulter Cays (now a globally Important Bird Area), and the Berry Islands. The census filled in a huge gap in our understanding of these engaging and imperiled birds.

Taking Part in the 2016 International Piping Plover Census

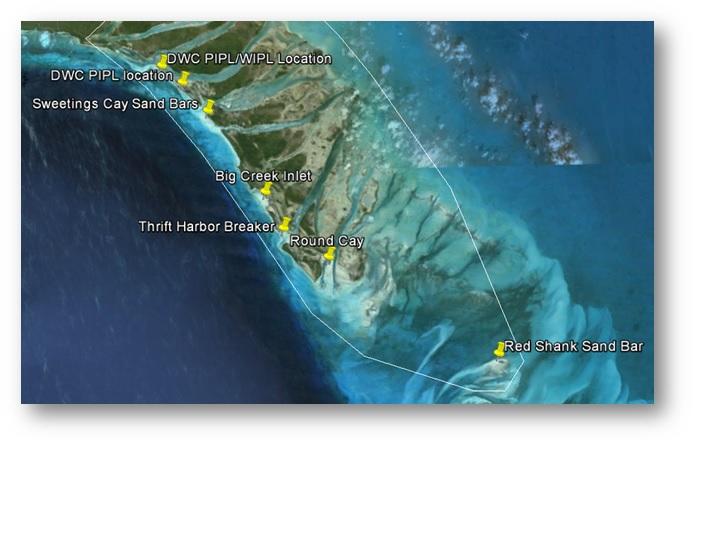

In January 2016, with support from the International Alliances Program, National Audubon Society staff from along the Atlantic Flyway, including Audubon Alliance staff member, Corrie Folsom-O’Keefe, pitched in to help with the 2016 International Piping Plover Census. From January 18–23, Corrie teamed up with Audubon New York’s, Amanda Pachomski, in surveying the cays at the east end of Grand Bahama Island. The pair traveled by flat-bottom skiffs and on foot, inventorying shorebirds and other waterbirds on sandbars, mudflats, and along the edges of mangrove islands.

Grand Bahama Island sits approximately 100 miles to the east of West Palm Beach, Florida. At the east end of the Island, large cays stretch out to the southeast, with creeks flowing between them. The shoreline along the western side of the cays includes stretches of sandy beaches and bars, vegetated flats, and limestone formations, while the eastern shoreline of the cays, with the exception of Rumer Flats, is mangroves.

“Over the course of our four days of surveys of the East Grand Bahama Cays, we learned that Piping Plover and Wilson’s Plover can be found along the entire western side if you look closely enough.” Says Folsom-O’Keefe, “Some areas are used for foraging a low tide (Sweetings Cay Flats, Big Creek Inlet, Round Cay, and Redshank), while other areas are high tide roosting spots (Deep Water Cay shoreline, shoreline between Big Creek Inlet and Thrift Harbor). At high tide, both Piping and Wilson’s Plover will use spots with just several meters of sandy beach. Wilson’s seems willing to use sections of rocky shoreline as well. All total, we detected between 17-18 Piping Plovers and 7 Wilson’s Plovers.”

“We also were able to locate good numbers of both Short-billed Dowitcher and Black-bellied Plovers.” reports Pachomski. “These birds seem to forage in mixed flocks at low tide on vegetated flats on the western side and muddy flats on the east side of the cays. We had an enormous flock of Short-billed Dowitchers at the East End Flats (450+) and flocks of approximately 200 Short-billed Dowitchers at the Brush Cay flats on the west side, and at Rumer Flats on the east side.”

Discovering More than Plovers

All of Grand Bahama has an interesting tidal cycle. When it is low tide on the south side of Grand Bahama (west side of cays), it is high tide on the north side of Grand Bahama (east side of cays). Ellsworth Weir of the Bahamas National Trust noted this is thought to be because the sides are linked through underwater caves. “It is possible that birds of East Grand Bahama, take advantage of the tides and travel from one side of the cays to the other to forage on exposed mud and sand flats every 6 hours, versus sticking to one side and only foraging every 12 hours. We suspect that the birds using Brush Cay and Rumer Flats may be the same birds, as the number of Dowitchers and Black-bellied Plovers was very similar,” notes Folsom-O’Keefe. “All total, we feel that we observed 725-965 Short-billed Dowitchers and 144-184 Black-bellied Plovers.”

Folsom-O’Keefe and Pachomski found 11 different types of shorebird species and observed 6 different types of long-legged waders. Semipalmated Plover, Dunlin, and Ruddy Turnstonea were often mixed in with Short-billed Dowitcher/Black-bellied Plover flocks.

American Oystercatchers were typically found in pairs or small groups on rocky outcroppings (Black Rock), on vegetated flats (thrift Harbor and East End Flats), or sand bars (Red Shank). Solitary Spotted Sandpiper were along rocky/sandy sections of the western shoreline. The only place they had Western and Least Sandpiper was Big Creek Inlet. Here the sandpipers huddled amongst rocky outcroppings in the middle of the flats.

Great Blue Herons (38 birds) and Great Egrets (49 birds) were the most common long-legged waders. They were found along the edges of the creeks, and also on mud flats adjacent to mangroves at low tide. “We were also able to locate a flock of 9 Tri-colored Herons,” says Folsom-O’Keefe. “We had just a few Little Blue Herons, and one each of Reddish Egret and Snowy Egret.”

In addition to shorebirds and long-legged waders, Folsom-O’Keefe and Pachomski observed 13 types of songbirds, 4 gull species, Royal Terns, Brown Pelican, Double-crested Cormorant (nesting colony on Jacob Cay), Belted Kingfisher, Osprey, Red-tailed Hawk, Osprey, and a Tundra Swan.

“The East Grand Bahama Cays, now a National Park, are a beautiful spot.” Exclaims Pachomski, “Besides birds, we also saw many rays (stingrays and leopard rays), sharks (one was a lemon shark), barracuda, bonefish, several types of echinoderms, and a variety of other fish and marine life.” Both Folsom-O’Keefe and Pachomski were thrilled to participate in the 2016 International Piping Plover Census and hope that the data they collected contributes to Piping Plover conservation efforts.